Prenatal exposure to synthetic sex hormones – including diethylstilbestrol – as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorders

DES (a widespread abbreviation for diethylstilbestrol, a synthetic estrogen), has been marketed in the 1950s in many countries by different pharmaceutical companies (UCB Pharma, Borne, Eli Lilly...), under different brand names (Distilbene®, Stilboestrol-Borne®, Furostilboestrol®...) This drug, advertised as a new "miracle drug", has been widely prescribed in France and abroad to pregnant women mainly to prevent miscarriages and premature labor, and related complications of pregnancy. The exact number of women who have taken DES during their pregnancy(s) is unknown, but it has been estimated that over 10 million people have been exposed around the world, including around 200,000 women in France.

DES has also been prescribed for other indications (learn more about DES indications on our "What is DES?" page), and sometimes combined with synthetic progestins.

In order to know the number of people impacted by DES exposure in France, D.E.S is it has launched a large national census which can be found on the following page: French national census of diethylstilbestrol victims

Although its efficiency has never been proven for any of its indications, its deleterious effects have been widely demonstrated.

Indeed, since its contraindication in pregnancy in 1971 by the FDA (DES continued to be prescribed until 1977 in France), studies have shown that DES has caused health problems not only in children exposed in utero, but also in their children: the third generation.

Diethylstilbestrol is, in fact, a powerful endocrine disruptor chemical (EDC).

The US EPA defines an EDC as "an exogenous agent that interferes with the synthesis, secretion, transport, metabolism, binding, or elimination of natural blood-borne hormones that are present in the body and are responsible for homeostasis, reproduction, and developmental processes."

Endocrine disruptors have been associated with numerous health effects, including: abnormalities of the male and female reproductive systems, development of obesity, cancer, neurodevelopmental disorders (especially after in utero exposure).

Diethylstilbestrol and autism?

Presentation of the article “Diethylstilbestrol and autism”

The article we will discuss today is entitled "Diethylstilbestrol and autism". It is written by Soyer-Gobillard and al. and has been published in the journal Frontiers in Endocrinoly in November 20221. It is a review of the existing literature, based on studies published for the most part between 2010 and 2022, and selected from PubMed and Google Scholar search engine results, using the following keywords (which we have translated): diethylstilbestrol, diethylstilbestrol and ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorders), progestins, progestins and ASD, psychosis and endocrine disruptors, and estrogen and epigenetics. So this is not a new study on the transgenerational effects of DES. And, in fact, despite its title, this is not an article that deals exactly with diethylstilbestrol and autism.

In this review, the authors observe that the prevalence of ASD has increased significantly, and suggest that environmental factors could be added to the list of its possible etiologies.

The authors hypothesize that prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) and other synthetic sex hormones "contributes to the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders, particularly autistic disorders".

We will now present the main studies described in this review, allowing the authors of "Diethylstilbestrol and autism" to support this hypothesis.

And, insofar as the authors include ASD in the psychiatric disorders, we will, in a second part, dwell on to the definition of autism.

DES and psychiatric disorders

In this review, Soyer-Gobillard and al. note that very few studies have examined "DES effects on neurodevelopment and psychiatric disorder occurrence, especially Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD)" (we quote here the authors), in children exposed in utero (2nd generation) and their descendants (3rd generation).

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then describe a 2010 American epidemiological study by O'Reilly and al. (Nurses' Health Study)2. This study involved 76,240 women, of whom 1,612 were exposed in utero to the drug. The results suggest that women exposed to DES in utero have an increased risk of depression in adulthood.

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then detailed the results of two of their previous studies3,4, which reported psychiatric effects occurring in adolescents/adults exposed in utero to DES from the Hhorages-France association's family database: in particular schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, depression, eating disorders, suicide attempts and suicide.

Hhorages-France (Halte aux HORmones Artificielles pour les GrossessES), is a French association founded in 2002 whose aim is to establish the causal link between the use of synthetic sex hormones during pregnancy and psychiatric disorders, whether or not associated with somatic disorders, in the exposed children. Hhorages-France has also self-published a book entitled "Resilience: a scientist's campaign against synthetic hormones" to which we devoted a previous article.

Compared to the general population, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the exposed group is significantly higher. This can be partly explained by the fact that the database used in these two studies is made up of families who are members of the association, which they may have joined precisely because of the presence of psychiatric disorders.

Recently, Soyer-Gobillard and al. described an informative family whose mother was prescribed DES to dry up her breast milk after each of her 11 pregnancies. Although not directly exposed, 10 of her children born after taking such a treatment had psychiatric disorders.

We quote here, once again, the authors: "in the third generation, 10/19 DES-exposed grandchildren had psychiatric disorders, especially ASD, Asperger syndrome or ASD without Asperger syndrome (in boys) and bipolar disorders for girls, associated with dyspraxia and learning disabilities, mood and behavioral disorders and eating disorders, as well as somatic comorbidities".

These studies5,6 suggest that DES is so potent that it is not eliminated from the body between the time it is stopped and the next pregnancy.

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then inform us that in utero exposure to other synthetic sex hormones such as ethinylestradiol (one of the components of the birth control pill) and synthetic progestins increase the risk of bipolar disorder/depression and schizophrenia.

The two articles7,8 cited here were based on data from the Hhorages-France cohort.

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then describe a study by Liu and al.9 demonstrating an association between the SOX2-OT gene and bipolar disorder with comorbid eating disorders. These findings support the involvement of neurodevelopmental/neuroprotective mechanisms in the pathophysiology of both disorders.

They specify right after that different authors, Remnelius and al.10, Carpita and al.11, Saure and al.12, Westwood and al.13 have reported a link between ASD and anorexia nervosa and have suggested a specific genetic link between anorexia nervosa and ASD.

Synthetic Progestins and Psychiatric Disorders

Soyer-Gobillard et al. cite également une étude de Soyer-Gobillard et al.14 dans laquelle les auteurs ont rapporté des effets psychiatriques faisant suite à une exposition prénatale aux progestatifs.

Synthetic Progestins and ASD

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then introduce us to a 2017 study by Zou and al.15, in which the authors demonstrated that in rats, exposure to levonorgestrel (a synthetic progestin) or a combination of levonorgestrel and ethinylestradiol (a synthetic estrogen) – both molecules used in oral contraceptive pills – induced "autistim-like" behavior in offspring, i.e., similar to the behavior of an autistic individual.

This behavior is much more pronounced in male offspring than in female offspring.

This occurs through levonorgestrel's inhibition of the expression (inactivation) of an estrogen receptor "ERβ" in the amygdala.

Ethinylestradiol alone does not induce autism-like behavior.

Soyer-Gobillard and al. then present a large epidemiological study by Li and al.16, published in 2018, which confirmed the above findings, i.e., that prenatal progestin exposure is associated with ASD.

The Li and al. study this time involved human subjects from Hainan Island, China. From 37,863 children, they selected 235 children with ASD, and 682 typically developing subjects as the control group.

The participants or their parents all completed the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ) form. Children with the following comorbidities were excluded: psychiatric symptoms, history of ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), epilepsy, depression, or brain injury. Participants were assessed using the Autism Behavior Checklist (ABC). The diagnosis of ASD was based on clinical assessments and was confirmed by clinical psychologists and psychiatrists according to the DSM-V assessment criteria (a reference manual that we talk about below).

The data from Li and al. show that the following factors strongly impact the prevalence of ASD: progestin use to prevent threatened abortion, progestin contraceptive use at the time of conception, and prenatal consumption of progestin-contaminated seafood during the first trimester of pregnancy among the mothers of these children.

In China, combined oral contraceptives (usually a combination of estrogen and synthetic progesterone) are, according to the authors, currently used by the seafood industry to prevent fish and shrimp from becoming pregnant, thus making them bigger (for more profits, certainly).

To test their hypothesis, Li and al. exposed a zebrafish to large amounts of progestin to mimic chronic exposure of seafood to the contamination. They then used this fish to feed pregnant rats, and found that their offspring exhibited behavior similar to that seen in autism.

The authors, Li and al, therefore conclude that prenatal progestin exposure is strongly associated with the prevalence of ASD, which was confirmed in the rat experiments.

This study by Li and al. is very interesting and we invite you to read it in its entirety.

It should be noted that synthetic progestins should not be confused with progesterone, which is a hormone naturally produced by the body.

For information, synthetic progestins can also cause meningiomas in women. A meningioma is a tumor that arises from the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. These meningiomas are considered benign because they are not cancerous. Nevertheless, these tumors are difficult to treat and sometimes require surgery. They can have significant consequences in the lives of those affected.

To learn more, we invite you to visit the website of the French association Amavea (Association Méningiomes dus à l’Acétate de cyprotérone, aide aux Victimes Et prise en compte des Autres molécules) at: https://amavea.org.

ADHD in the DES Third-Generation

The next study in this review is entitled "Association of Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol During Pregnancy With Multigenerational Neurodevelopmental Deficits," and was published in 2018.

The authors, Kioumourtzoglou and al.17, demonstrate that DES exposure is associated with neurodevelopmental deficits.

Indeed, their study reveals that children whose grandmother took DES during pregnancy are 36% more likely to have Attention Deficit Disorder with or without hyperactivity (ADHD). These results do not differ by gender. They are statistically highly significant.

When DES was taken during the first trimester of pregnancy, the risk for grandchildren is even greater, rising to 63%.

When DES was taken in the 2nd and 3rd trimester, as well as when the trimester is unknown, the results are not statistically significant.

If this is not the only possible mechanism, the biological mechanism is probably an epigenetic transgenerational effect, i.e. a change in the way genes are expressed.

Thus, the first trimester of pregnancy may represent a critical window of vulnerability to DES exposure.

Genetic alterations common to schizophrenia and autism

The hypothesis of a neurodevelopmental etiological mechanism of schizophrenia has been put forward several times, but a possible neurodegeneration or "neurotoxicity" at the onset of the disease is still discussed, because early neurodevelopmental damage are not enough to explain the late onset of schizophrenic symptoms18.

The authors, Soyer-Gobillard and al, then cite a 2017 study (previously discussed on our blog) by Rivollier and al.19 published in the journal PLOS One, which found changes in the expression of two genes in psychotic patients exposed in utero to DES: the ADAMTS9 gene and the ZFP57 gene. These two genes could influence fetal neuroplasticity.

The ADAMTS9 gene plays a role in controlling the shape of sex organs during development and inhibiting angiogenesis (the process of growing new blood vessels from pre-existing ones)20. The ADAMTS9 gene is also involved in the development of the brain.

Methylation (expression) abnormalities of this gene have been observed in gastric, colorectal and pancreatic cancers. It is a gene that may play a role in central nervous system development.

The protein produced by the ZFP57 gene belongs to the family of zinc finger proteins, which are involved in many cellular functions. Therefore, according to the authors, the alteration of the expression of this gene can have many consequences, especially during neurodevelopment.

The authors Rivollier and al. rely on a 2013 study, in which this same ZFP57 gene was found more methylated in autistic patients than in the control group, to say that both autism and schizophrenia are linked to deviant neurological development and plasticity.

They add that schizophrenia and autism have common characteristics, based on two publications highlighting a supposed developmental continuum between these disorders, and on the link between ASD and childhood schizophrenia, which the long history of autism and its classification has however allowed to discriminate.

However, this study is very important because it proves that diethylstilbestrol exposure can have consequences on gene expression, which can be detected in the blood.

Autism and genital malformations

The authors, Soyer-Gobillard and al., then present several studies (Chen and al.21, Rotem and al.22, Bodur and al.23) reporting that there is a correlation between genital malformations (disorders of sex development) and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Genital malformations, such as cryptorchidism (undescended testicle) or hypospadias (abnormal position of the urinary meatus) in males, and structural abnormalities of the uterus in females, are very common in persons exposed in utero to DES. Similar malformations are also found in the third generation of victims.

The authors of the review have identified in a preliminary work, in the Hhorages-France cohort, several girls and boys with both ASD and disorders of sexual development.

Conclusion

We strongly believe that there is a link between exposure to DES, to synthetic sex hormones and, more broadly, to endocrine disruptors, and neurodevelopmental disorders, including ASD – without excluding other factors, such as very preterm birth.

However, this is not a review that deals exactly with DES and autism. And we do not learn anything new on this subject since the informative family – whose mother received DES after each of her pregnancies and where ASD is found in the grandchildren – was described in a previous publication.

Only the sequence of the different parts and subjects manage to create the illusion of the demonstration of a relationship (a link that we do not however question!), between DES exposure and autism: DES and psychiatric disorders, bipolarity with APD and gene, ASD with APD and genes, progestins and psychiatric disorders, progestins and ASD, ADHD and DES, genetic disorders common to schizophrenia and ASD, ASD and genital malformations.

We have not critiqued the articles that this review presents as we go along so as not to impede your reading. Nevertheless, we have deliberately put some words in bold to emphasize that the authors define autism as a psychiatric disorder, which it is not.

Soyer-Gobillard et al. invite us all to apply the precautionary principle for the protection of future generations: women must remain vigilant regarding synthetic sex hormones, whether or not they are pregnant.

History of the concept of autism

Autism was not defined until 50 years ago. Two socio-historical phenomena participated upstream in the birth of the concept of autism:

- the compulsory education for all children, because it was then necessary to manage the children and their interactions, which made it possible to note that with some it was more difficult to interact.

- around the 17th century, the birth of psychiatry as a scientific discipline with the introduction of the notion of curable mental illness and the establishment of the first classification of mental illnesses by Dr Philippe Pinel.

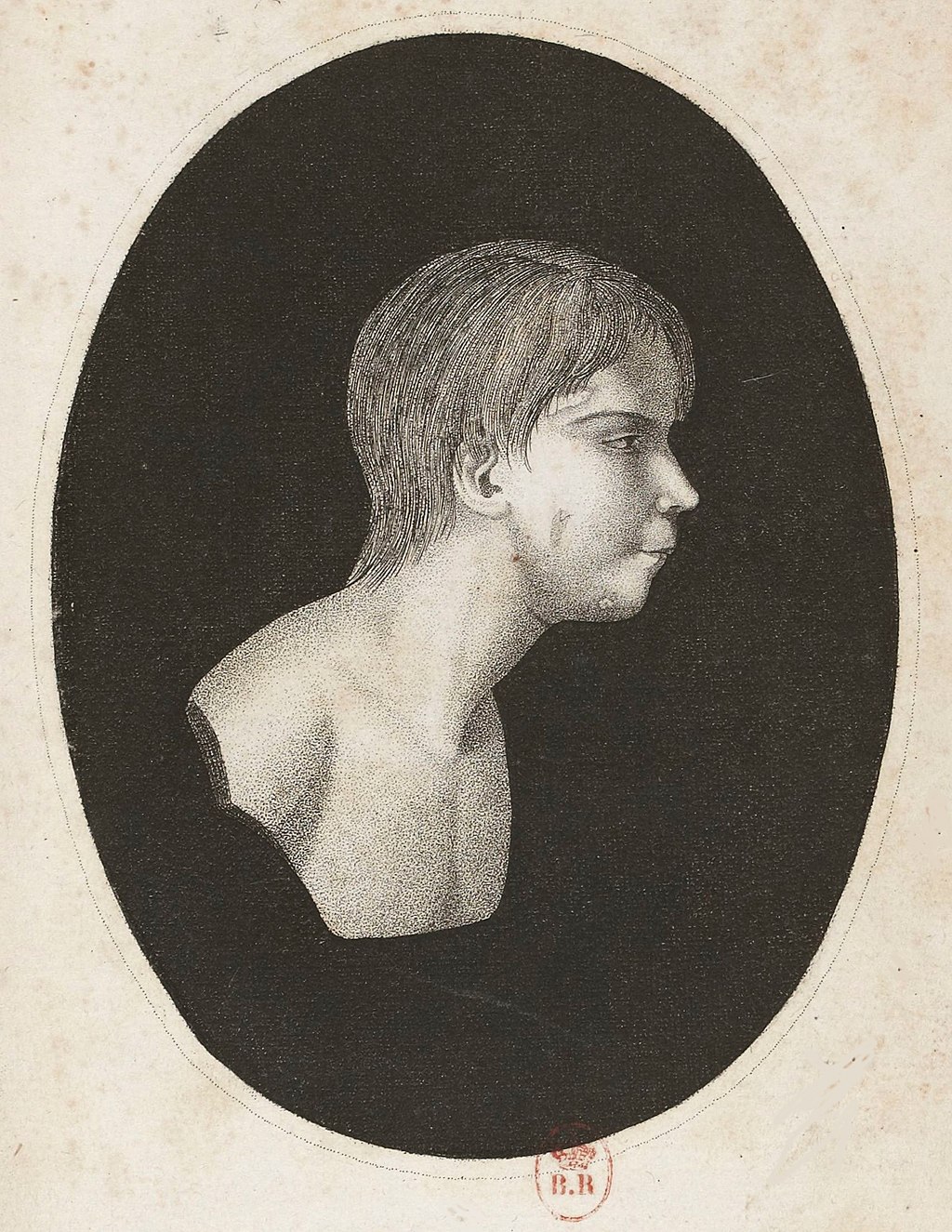

Dr. Philippe Pinel was particularly interested in melancholy, dementia and what he called "idiocy", i.e. an "obliteration of the intellectual faculties and affections.".

In 1797, a "wild child" about eleven or twelve years old was found in the forest, in Aveyron, France. He does not speak and his gestures were unusual. At first, he was thought to be deaf and dumb, before being transported to Paris to the Bicêtre hospital, where Doctor Philippe Pinel described him in a report as mentally ill and idiot from birth.

Jean-Marc Itard, one of his students, who was particularly interested in the suffering of children, suggested to his teacher that some children were not in fact idiots, and could also be brought to an education, especially a moral one.

He will thus propose to Dr. Pinel to conduct an experiment consisting in educating this young boy – nicknamed Victor de l'Aveyron –, who is the first child thought to have had characteristics of autism: a difficulty in communicating by language and signs, an impossibility to establish social relations, repetitive gestures and restricted interests.

Despite his relative failure, Jean-Marc Itard's approach was historic and helped to understand the concept of developmental windows: certain acquisitions must take place earlier in development, particularly language.

Since this child was already a dozen years old, there was little room for maneuver. This is why there is currently a lot of talk about the importance of an early diagnosis and therefore and therefore an early care. A multidisciplinary care adapted to each individual is likely to improve the quality of life of autistic people.

It is obviously impossible to state with certainty that this child was autistic as we know nothing about his past. However, the anamnesis plays an essential role in the diagnosis of autism. Therefore, it is not impossible that he may have suffered from hospitalism and/or abuse. Nevertheless, based on Jean-Marc Itard's reports, several psychiatrists have retrospectively made a diagnosis of autism.

Eugene Bleuler, a 20th century Swiss psychiatrist – who coined the term "schizophrenia" (schizo meaning "schism", and phrenia "of the mind") – was the first to use the word "autism". "Autism" comes from the ancient Greek αὐτός, which means "self" and characterizes inward-looking behavior.

Eugene Bleuler introduced the term in 1911 in his book Dementia praecox or group of schizophrenias, and used it to refer to schizophrenic adults who are withdrawn into themselves, into imagination. The word "autism", at that time, was therefore used not to designate problems of communication and social interaction, but as a characteristic of psychosis.

From 1920 onwards, with the generalization of compulsory education, researchers and clinicians became more interested in the suffering of children. There was a need to understand and identify children who were unable to follow the courses given or who were likely to disrupt classes.

This is how Bleuler's concept of schizophrenia was applied to the child: a child caught up in his thoughts, his imagination, was characterized as a schizophrenic child. Indeed, for the researchers and clinicians of the time, hallucination is a characteristic of schizophrenia, and the child is potentially, here, hallucinating.

In 1938, Louise Despert, an American psychologist, described in an article cases of schizophrenic children. The reported behaviors (asociability, withdrawal, fear of new emotional contacts, irritability, tendency to daydream, to live in their own world...) are today attributed to autism.

Louise Despert described two forms of appearance of these behaviors: a sudden and acute form, and an insidious and progressive form. She hypothesizes that schizophrenia is present from birth. This contradicts the psychoanalytical theses which affirm that a time of normal development always precedes the arrival of schizophrenia in a child.

In 1943, an article by Leo Kanner, an Austrian and American child psychiatrist, describes for the first time 11 cases of autistic children. His description was very similar to that of Louise Despert, but he insisted on several things: autism is different from schizophrenia, and the autistic child do not hallucinate.

Gradually, he clarified his definition of childhood autism. He describes the particularities of communication with: repetitions, monotonous acts and words and delayed echolalia. He describes a literal comprehension, an inability of these children to establish relationships, to initiate interaction, and thus a "problem in establishing an emotional bond with others".

He describes a restriction of the children's sphere of interest and points out an "anxious obsession" with permanence and a form of intolerance of uncertainty.

He also assumes that, unlike schizophrenia, childhood autism is present from the beginning of life.

Despite this publication by Leo Kanner, autism remained associated with childhood schizophrenia until the 1970s, when changes took place. While the diagnostic practice was psychoanalytical, its approach was now based on observable criteria. Also, research in psychiatry evolved and favoured statistical models and the study of the prevalence of disorders. Research in psychology also progressed.

In 1980, the DSM-III (American classification of mental disorders) recognized autism as a disorder in its own right. It is described in a category called "pervasive developmental disorder", thus highlighting its developmental nature. Autism is found alongside childhood psychosis, but is clearly differentiated. The criterion of "withdrawal" observed in schizophrenics was removed in this version of the DSM.

Between 1980 and 1990, Lorna Wing, an English child psychiatrist, put forward the hypothesis that in autistic children, a certain number of cerebral areas, which process social information and manage communication faculties, are vulnerable. She defined autism, not as an affective disorder as Leo Kanner thought, but as a developmental disorder of social communication and interaction.

In 1981, she updated the work of Hans Asperger – an Austrian psychiatrist, author of a pioneering study on autism – and made a proposal to define Asperger syndrome. She presents a triad of characteristics that are more recurrent in Asperger's syndrome and autistic disorders, which would later be used to define several levels of disability specific to autistic people: abnormalities in social interactions, abnormalities in verbal and non-verbal communication, and restricted interests.

Lorna Wing's work had a great influence since in 1994, Asperger's syndrome was added to the DSM-IV, as well as the autistic triad of impairment (social interaction disorders, social communication disorders and repetitive and restricted behaviours) in the diagnostic criteria.

It took almost 100 years to differentiate autism from psychosis, to understand it, and to define it24.

Current classification and definition of autism

In the DSM-V (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition), published in 2013, disorders that appear in childhood are now taken into account from a developmental and longitudinal perspective. Thus, a specific chapter is devoted to neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD) and the definition of an "autism spectrum disorder" (ASD).

Neurodevelopmental disorders include attention deficit disorder, intellectual development, motor skills, communication and learning.

Within the neurodevelopmental disorders, however, ASD has unique characteristics that make it a diagnostic category in its own right.

The diagnosis of "Asperger's Disorder" no longer exists in this version of the DSM, so individuals with Asperger are now included in ASD.

In order to avoid overlap between social interaction disorders and social communication disorders, the triad of impairment (triangle of issues) has been changed to a dyad (2 pillars of issues): social communication deficits (combining social and communication problems), repetitive and restricted behaviors. In addition, unusual sensitivity to sensory stimuli (hypersensitivity/hyposensitivity) are frequently observed in autism. Finally, the DSM-V encourages early diagnosis.

Other new features of the DSM-V include acne excoriation disorder (dermatillomania: people with this disorder repeatedly scrub their skin, causing sores), compulsive hoarding disorder (syllogomania), and the completion of criteria for caffeine withdrawal syndrome.

The DSM now favours a so-called dimensional approach, in particular through the use of rating scales to measure the severity of symptoms.

The ICD-11 (International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) came into effect in January 2022.

The diagnostic criteria for autism have been updated to be more in line with the DSM-V. Its chapter 6 is dedicated to mental, behavioral and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Overall, the two classifications, DSM-V and ICD-11, are very similar and the objective of harmonization has been achieved.

We take up here the general definition of autism proposed by the Centre de Ressources Autisme Île-de-France (CRAIF):

"Autism is not a mental illness. It is a neurodevelopmental disorder: that is, brain alterations that occur before birth and that affect language, motor skills, perception, emotions, social interactions...

This is why, since 1996, autism has been officially recognized as a handicap."

As well as the definition of ASD by the Centre de Ressources autisme Rhône-Alpes:

"Autism is defined as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by disturbances in social interactions, communication and by behaviors, interests and/or activities with a repetitive and restricted character. [...] The characteristics of autism vary greatly from one individual to another and cover a broad spectrum. This is why today, physicians and professionals trained in autism use the term Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)."

We also remind you that the diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) must be made by a medical doctor (family physician, pediatrician, child psychiatrist, psychiatrist, neurologist...).

Frequent Comorbidities with ASD

These are the various disorders that are frequently associated with ASD. The most common coexisting health condition are:

- Attention Deficit Disorder with/without Hyperactivity (ADHD): children with ADHD are 30 times more likely to be diagnosed with ASD after the age of 625.

- Intellectual disability: of varying severity, it affects one-third of people with ASD26.

- Genetic disorders: Fragile X syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis complex, Neurofibromatosis, Angelman syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome…26

- Learning disability: these are all "DYS" disorders: dysphasia (difficulties gaining language skills), dyslexia (difficulties learning to read), dysorthography (difficulties gaining spelling skills), dyscalculia (difficulties gaining arithmetic skills, dyspraxia (difficulties gaining motor skills).

- Sleep disorders: these may be linked to reduced levels of melatonin and circadian rhythm abnormalities.

- Psychiatric disorders: depression, anxiety…

- Epilepsy: it is more common in autistic people with mental retardation, with a prevalence that is all the higher as the retardation is important27.

- Vitamin deficiencies : vitamin D, vitamin B12, vitamin B9, vitamin A, zinc, magnesium and calcium.

To go further

- [In French] Donwload Comprendre le diagnostic d’autisme de mon enfant – A guide for parents and caregivers, produced by the Groupement National Centres Ressources Autisme: https://gncra.fr/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Brochure-Post-Diag-Enfant-GNCRA-Web.pdf

- [In French] Donwload Mon guide d’accompagnement : autisme, produced by le Collectif Inclusif visant à accompagner la scolarisation des jeunes enfants TSA: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-1ItVIvTw38k3IVP2d9CFEa9q16XBwAa/view

- [In French] Donwload the brochure L'autisme au féminin : brochure à destination des professionnels de santé, made by le Groupe d'Action Autisme au Féminin (GRAAF) in partnership with Autisme Info Service : https://www.craif.org/lautisme-au-feminin-brochure-destination-des-professionnels-de-sante-223

- [In English] Watch the hand-drawn animated movie MIND MY MIND by Floor Adams, about a young man on the autism spectrum: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffzbIvVbepg

- [In French] Watch the documentary film Quelle folie, by Diego Governatori, with Aurélien Deschamps: https://www.allocine.fr/film/fichefilm_gen_cfilm=273124.html.

Notes & references

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Courtet P, Sultan C. Diethylstilbestrol and autism. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Nov 21;13:1034959. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1034959. PMID: 36479217; PMCID: PMC9720308.

- O'Reilly EJ, Mirzaei F, Forman MR, Ascherio A. Diethylstilbestrol exposure in utero and depression in women. Am J Epidemiol (2010) 171:876–82. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq023

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Paris F, Gaspari L, Courtet P, Sultan C. Association between fetal DES-exposure and psychiatric disorders in adolescence/adulthood: evidence from a French cohort of 1002 prenatally exposed children. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2016;32(1):25-9. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1063604. Epub 2015 Jul 14. PMID: 26172930.

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Sultan C. Behavioral and somatic disorders in children exposed in utero to synthetic hormones: A testimony-case study in a French family troop. In: M. S, editor. State of the art of therapeutic endocrinology. Japan: InTech (2012). p. 67–86.

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Paris F, Kalfa N, Hamamah S, Courtet P, et al. Prenatal exposure to diethylstilbestrol and multigenerational psychiatric disorders: An informative family. Int J Environ Res Public Health (2021) 18(19):9965. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18199965

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Sultan C. Consequences of In utero exposure to synthetic estrogens and progestogens for children and grandchildren. IJCIMR (2021) 14:001–5. doi: 10.55920/IJCIMR.2021.01.0001001

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Sultan C. Evidence for a link between in utero exposure to synthetic estrogens and progestins and mental disorders: A long and crucial history. In: A.L. Woolfolk R, Durbano F, Irtelli F, editors. Psychopathology : An international and interdisciplinary perspective. London: IntechOpen (2020). p. 7–22

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Yao P, Sultan Ch. Prenatal exposure to progestins: Impact on neurodevelopment of the child. In: P.V. Martin C, Rajendram R, editors. Factors affecting neurodevelopment. London: Academic Press (2021). p. 395–408.

- Liu X, Bipolar Genome S, Kelsoe JR, Greenwood TA. A genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder with comorbid eating disorder replicates the SOX2-OT region. J Affect Disord (2016) 189:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.029

- Lundin Remnelius K, Neufeld J, Isaksson J, Bolte S. Eating problems in autistic females and males: A Co-twin control study. J Autism Dev Disord (2022) 52:3153–68. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05198-z

- Carpita B, Muti D, Cremone IM, Fagiolini A, Dell'Osso L. Eating disorders and autism spectrum: Links and risks. CNS Spectr (2022) 27:272–80. doi: 10.1017/S1092852920002011

- Saure E, Laasonen M, Raevuori A. Anorexia nervosa and comorbid autism spectrum disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2021) 34:569–75. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000742

- Westwood H, Eisler I, Mandy W, Leppanen J, Treasure J, Tchanturia K. Using the autism-spectrum quotient to measure autistic traits in anorexia nervosa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord (2016) 46:964–77. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2641-0

- Soyer-Gobillard MO, Gaspari L, Courtet P, Puillandre M, Paris F, Sultan C. Neurodevelopmental disorders in children exposed in utero to synthetic progestins: Analysis from the national cohort of the Hhorages association. Gynecol Endocrinol (2019) 35:247–50. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2018.1512968

- Zou et al. Zou Y, Lu Q, Zheng D, Chu Z, Liu Z, Chen H, et al. Prenatal levonorgestrel exposure induces autism-like behavior in offspring through ERbeta suppression in the amygdala. Mol Autism (2017) 8:46. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0159-3

- Li L, Li M, Lu J, Ge X, Xie W, Wang Z, et al. Prenatal progestin exposure is associated with autism spectrum disorders. Front Psychiatry (2018) 9:611. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00611

- Marianthi-Anna Kioumourtzoglou, ScD, Brent A. Coull, PhD, Éilis J. O’Reilly, ScD, Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, and Marc G. Weisskopf, PhD, ScD - Association of Exposure to Diethylstilbestrol During Pregnancy With Multigenerational Neurodevelopmental Deficits - JAMA Pediatr. 2018 Jul; 172(7): 670–677.

- KREBS Marie-Odile, « Chapitre 4. Modèles physiopathologiques : modèle neurodéveloppemental, maturation cérébrale et « double hit » », dans : , Signes précoces de schizophrénie. Des prodomes à la notion de prévention, sous la direction de KREBS Marie-Odile. Paris, Dunod, « Psychothérapies », 2015, p. 53-66. DOI : 10.3917/dunod.krebs.2015.01.0053. URL : https://www.cairn.info/signes-precoces-de-schizophrenie--9782100738434-page-53.htm

- Rivollier F, Chaumette B, Bendjemaa N, Chayet M, Millet B, Jaafari N, Barhdadi A, Lemieux Perreault LP, Provost S, Dubé MP, Gaillard R, Krebs MO, Kebir O. Methylomic changes in individuals with psychosis, prenatally exposed to endocrine disrupting compounds: Lessons from diethylstilbestrol. PLoS One. 2017 Apr 13;12(4):e0174783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174783. PMID: 28406917; PMCID: PMC5390994.

- [Online] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/56999

- Chen J, Sorensen HT, Miao M, Liang H, Ehrenstein V, Wang Z, et al. Cryptorchidism and increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. J Psychiatr Res (2018) 96:153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.006

- Rotem RS, Chodick G, Davidovitch M, Hauser R, Coull BA, Weisskopf MG. Congenital abnormalities of the Male reproductive system and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Am J Epidemiol (2018) 187:656–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx367

- Gul H, Bodur Ş., Çetinkaya M, Taşkıran C, Işıldar Y. Findings of Male genital anomalies in a Turkish population with autism spectrum disorders. Anatolian Clinic J Med Sci (2019) 24:72–7. doi: 10.21673/anadoluklin.460738

- [Online] Troubles du spectre de l’autisme : diagnostic – Université de Genève, https://www.coursera.org/learn/troubles-spectre-autisme-diagnostic

- Miodovnik A, Harstad E, Sideridis G, Huntington N. Timing of the Diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics. 2015 Oct;136(4):e830-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1502. Epub 2015 Sep 14. PMID: 26371198.

- ↑ a ↑ b Dossier de connaissance – Les troubles du neurodéveloppement de 3 à 6 ans. Réalisé par Émilie Bec, Centre Régional d’études, d’actions et d’informations en faveur des personnes en situation de vulnérabilité. Novembre 2019. Read it at: https://creaiors-occitanie.fr/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/TND-3-6-ANS.pdf

- AMIET C, GOURFINKEL-AN I, CONSOLI A, PERISSE D, COHEN D. Epilepsie et autisme : une association complexe. Archives de pédiatrie 2010 ; 17 (6) : 650-651.